If you’ve ever wandered into a comment section under one of my videos showing a baby reading big red words, you’ve probably seen it:

“This is just the look-say method. It doesn’t work.”

A confident declaration—usually followed by a vague reference to “the science of reading.”

But here’s the thing: while both Doman’s method and the Look-Say method use whole words, equating them is misleading. It’s like saying a violin and a chainsaw are the same because they both have strings. Let’s break this down.

💬 What Was the Look-Say Method, Anyway?

The Look-Say method was popular in American schools from the 1930s through the 1960s. It taught reading by having children memorize whole words through repetition. This process was often paired with pictures and context clues. Books like “Dick and Jane” used a tiny pool of simple, repetitive words (“See Spot run. Run, Spot, run.”) and assumed children would gradually absorb reading through exposure.

The approach was simple, but it came under heavy criticism for skipping phonics and leaving struggling readers without decoding tools.

🧠 Doman’s Method: A Whole Other World

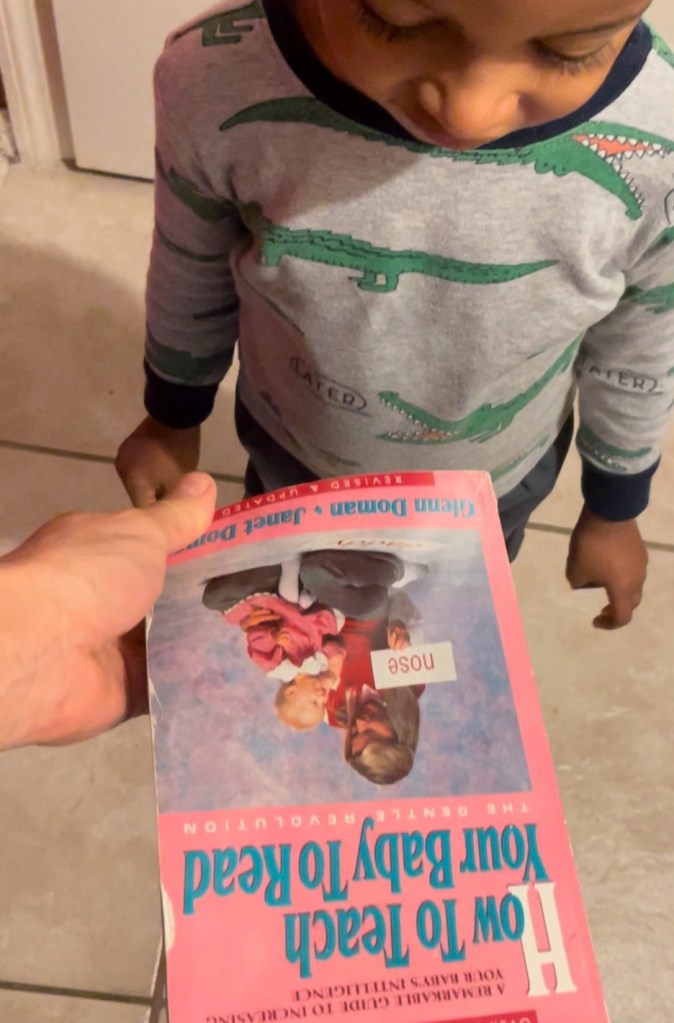

Now let’s look at Glenn Doman. His method also teaches reading through whole words—but the similarities stop there.

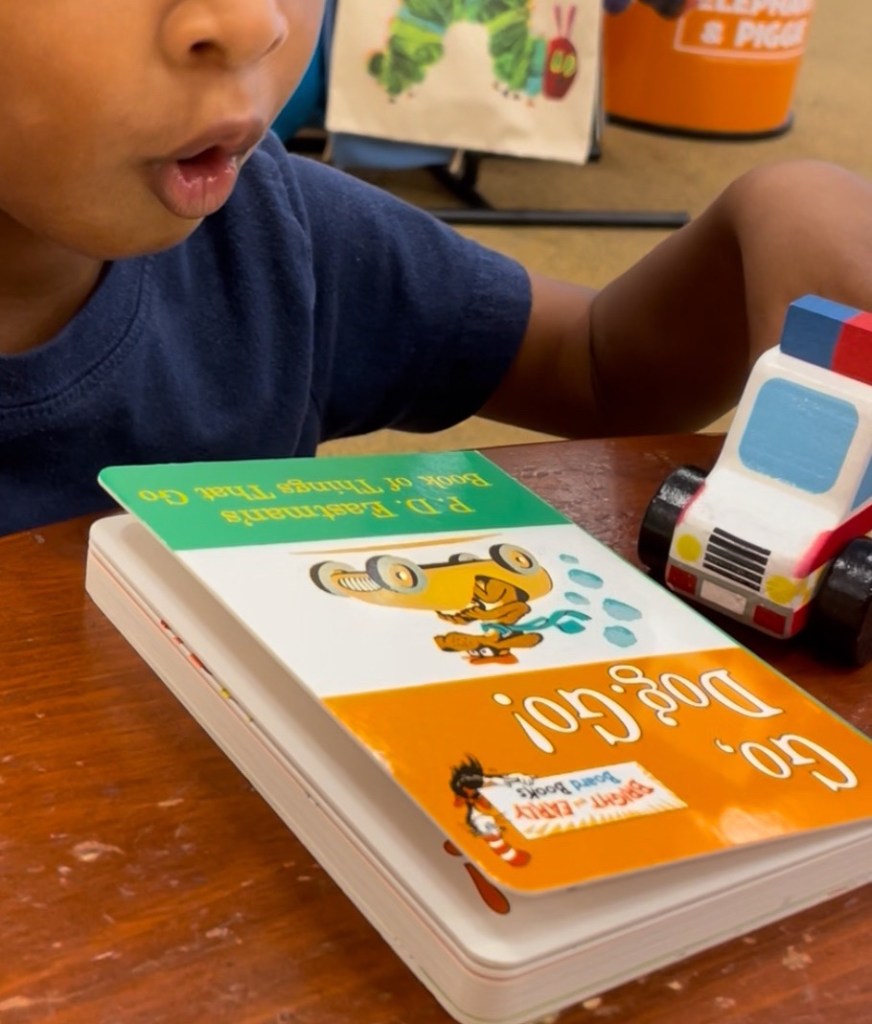

🔹 Audience: Doman’s method is for babies and toddlers, not school-aged children.

🔹 Purpose: It’s not just about reading. It’s about stimulating the developing brain in the first three years of life. This is when neural growth is at its peak.

🔹 Method: Words are shown quickly, clearly, and separate from pictures—deliberately avoiding guessing from context.

🔹 Vocabulary: Instead of “run” and “ball,” Doman encouraged teaching words like excavator, photosynthesis, and St. Bernard. Why? Because babies love big words, and they can handle them just fine.

🧪 The Science of Reading vs. the Science of Brain Development

Much of the criticism thrown at Doman’s method comes from a misunderstanding of the research. Critics rely on “the science of reading.” This approach is built around teaching children to decode written language. Typically, this begins at age 5 or 6.

But Doman’s work falls under a different umbrella: early brain development, not classroom reading instruction.

And here’s the kicker—there is no significant body of research focused on formal reading instruction for babies aged 0–3. What we do have is a mountain of research confirming that the brain is most receptive to input in the first three years of life. Doman’s method is about using that window to build strong neural networks, not preparing babies for spelling tests.

💡 So Is Doman’s Method Perfect?

No method is perfect. But dismissing Doman’s approach by calling it “look-say” is not only inaccurate—it misses the point entirely. This is not about replacing phonics in schools. It’s about recognizing the potential of the developing brain and offering stimulation at a time when it matters most.

Most critics haven’t tried the method. They haven’t sat down with a 1-year-old who lights up at seeing a word they recognize. And they certainly haven’t observed what happens when a child is trusted with meaningful input from birth.

❤️ Final Thoughts

If we truly want to support children’s learning, we have to stop shouting “science!” like it’s a weapon and start asking better questions. What if early reading isn’t about pushing academics too soon? Instead, it could offer joyful, brain-building experiences when a child is most open to learning.

So no, Glenn Doman’s method is not look-say. It’s a pioneering approach rooted in respect for a baby’s capacity to learn. And if you’ve ever seen a toddler read the word hippopotamus and giggle with pride—you already know that something powerful is happening.